Yesterday was a tough day in our family.

The family decision -- which was really my Mom's decision to honor Dad's wishes -- was that no artificial means will be used to prolong my Dad's life.

No feeding tube, no IV, nothing.

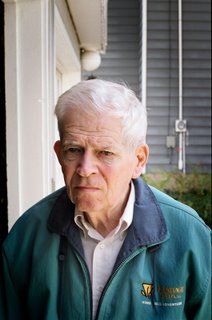

Even though his hastening death is something that we have all been preparing for since his stroke in 1999, how can you really prepare for the death of your father?

I was hoping that the feeding tube might be inserted and there might be a chance for "recovering" from this latest episode, but it is not what Dad wanted and I am okay with that as is everyone in the family. As hard as it is for us here to let go, we all know, deep down, that it is for the best.

He knows too. He won't open his mouth to be fed and strongly shook his head NO when my sister Mary asked him if he wanted a feeding tube implanted.

After seeing him just a couple of weeks ago here, there was a side of me that sensed as we said our goodbyes at the airport, that this was the last time I would see him alive.

But that didn't prepare me for the torrent of emotions that nearly doubled me over while my Mom informed me on the phone that no feeding tube would be implanted. She repeated it in a strong but calm voice almost to reassure her that she was doing the right thing (she is, I think) but almost as a way to say, Don't argue with me on this one thing (I won't).

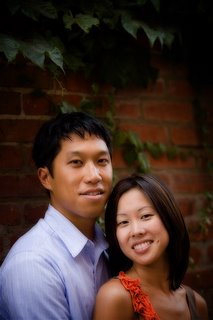

Poor Kate, laying on her mat looking up at me with her eyes wide in horror could only wonder why is Dad crying?

In some ways it feels like the man that was my Dad died with the stroke and yet the man that was left is now about to pass on.

But he hadn't died, he just changed, and deep down in his soul he was always the Dad the we knew and that's the reason for the sadness.

So we are preparing for his death, and we don't know when, though we will probably head to Wisconsin on the Fourth of July or close to that time. It will be the first time Kate will meet her aunts, uncles and some of her cousins. A good thing to come from the sadness.

I've been looking through some photographs and want to dig out some photos of Dad before he had the stroke, when he was younger, more vital, always a hard worker. I've got a picture that I want to find that I made of him amidst the dust and swirling seeds at his warehouse when he was mixing a ton of grass seed. I don't know how many of those tons I had mixed when I was a kid and in college and I remember being taken by the beauty of the scene and yet I felt a sadness that here he was doing this work in his sixties.

But the real pictures of my Dad that were never photographed with a camera only rest in the back of my mind as great images of who he was.

The first image is of Dad tossing me the baseball as we did all through the summers of my childhood after the sun had dropped below the trees. The ball, black from being tossed on the grass and bounced off the cement all summer (we only got one new ball a year) is now almost dangerous so we toss it against the sky (sometimes barely missing a winged bat) until it gets to be so dark that we can barely see. We head in, he puts his arm around my shoulder as we go in to make a root beer float.

The second image is of him coaching me in Little League when I was 10. It was a Saturday morning game and it was the bottom of the sixth -- our last chance to win. Somehow, the center fielder decided to play in on me and I smacked that thing over his head and he was still chasing it as I rounded third and then slid into home (I didn't need to, I just wanted to). We won, a walk-off home run and I remember looking up and seeing Dad over on the third base line, dancing like an warrior. One hand on the clipboard that held his scoring book (they're probably still at home somewhere) and the other hand punching the air, happy we won and probably more happy (he never said) that I hit the home run.

Finally, I will never forget the image of him at the train station at home in Columbus, as he was putting me on the Amtrak to return to Marquette for my last semester after five years of college. I was 22, and just could not wait to get out of school and into the workplace (I had lined up an internship in Chicago that summer that would turn into a job later) and I just didn't relish the thought of the 18 credit hours required for me to graduate.

I was ready to quit to just say enough. I half expected an argument, but instead I got a look of fatherly concern and support.

I know how you feel, it's been a long haul, he said. And I know it doesn't seem like it will ever end. But trust me, it will. You have come so far and it's going to be a tough semester but then it will be done and you will be able to look back on this and realize that you did it. You did what you set out to do. And in twenty years if you quit I think you'll always regret that you didn't just stick it out just a bit longer.

There was no anger, no threats, no intimidation, just a man talking to his son, who was now becoming a man. It was a turning point in our relationship and he was so right. I would regret it if I didn't, and that last semester was a struggle.

But I did it. And he taught me in those instances what parenting is about and they are the lessons I'll take with me, add my own twist and pass along to Kate.

Thank God she met him twice in her first sixth months. She may not remember it, but she will have the photographs and she'll have the stories of her grandfather, a man who's father died when he was five, who survived the depression, put himself through college by sleeping in the University greenhouse to save money, met a woman one night, told his best friend the next day that she would be his wife (sounds kind of familiar?) and they married and would be happily married for 50 years, fathered four children, grandfather to six and a good and decent man.

I'd say that is an amazing legacy.